Throughout history, human imagination has transformed our world with revolutionary inventions – from the humble wheel to the rise of artificial intelligence. Our species has a unique capacity to envision tools that extend our mind and body, enabling us to reshape reality.

“Man is a tool-using animal. Without tools he is nothing, with tools he is all.”

–Thomas Carlyle

As the Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle observed, “Man is a tool-using animal. Without tools he is nothing, with tools he is all.”

Each major breakthrough – fire, the wheel, writing, the printing press, electricity, the computer – has enhanced the human experience in profound ways. Yet, like any powerful tool, each was initially met with skepticism and fear. Today, as we stand on the cusp of the AI age, it is worth remembering how previous innovations advanced humanity despite early apprehensions. By examining our past—from the wheel to modern AI—we can better appreciate the incredible opportunity we have to improve life on Earth, and why we need not fear the tool itself, but rather the misuse of it.

Fire: Igniting Human Progress

Long before wheels or computers, our ancestors’ mastery of fire set humanity on a new trajectory. The controlled use of fire provided warmth, light, protection, and a way to cook food, which in turn made nutrients more accessible and diets more efficient. Some anthropologists even argue that cooking helped Homo sapiens develop larger brains and more complex societies. While debates continue about fire’s exact role in our evolution, its impact on civilization is undeniable. “Without a doubt, fire has proved a primary mover in the evolution of civilization,” driving countless advances from metallurgy to agriculture. By taming flame, humans could venture into harsh climates, forge tools and pottery, and gather in communal hearths to share stories and knowledge. Fire, one might say, was the first spark of technology that expanded the boundaries of human experience.

Importantly, fire was also the first technology that inspired awe and caution in equal measure. Ancient myths like that of Prometheus (who stole fire from the gods) underscore how powerful and ambivalent fire seemed to early people – it could cook meals and harden clay, but also burn homes and forests. Learning to use fire responsibly was one of humanity’s first ethical-technical dilemmas. Over time, we learned to respect rather than fear the flame, reaping its benefits while managing its dangers. This pattern – initial fear, eventual mastery – would replay with each subsequent invention, right up to modern times.

The Wheel: Rolling Humanity Forward

The oldest known wooden wheel (with its axle), over 5,000 years old, discovered in Slovenia. The invention of the wheel was a monumental turning point in human history, enabling people to transport goods and travel farther than ever before. Simple as it seems today, the wheel’s innovation helped “make history go around faster and faster,” revolutionizing agriculture, commerce, and communication.

If fire gave us control over energy, the wheel gave us control over motion. Invented in ancient Mesopotamia over 5,000 years ago, the wheel stands as one of humanity’s most transformative innovations. Early wheels were used on potter’s wheels to shape clay, and later adapted to carts and chariots, allowing people to move heavier loads over longer distances than ever before. This seemingly simple circular tool enabled large-scale transport of goods and produce, spurred the domestication of draft animals, and wove distant communities together through trade. In short, the wheel helped humans conquer distance and expand their world. It is no exaggeration to say the wheel “profoundly shaped the course of civilization,” becoming an enduring symbol of innovation itself.

At the time of its introduction, the concept of a rolling wheel on an axle must have felt almost magical—a leap of imagination turning a round slice of wood into an engine of progress. There is no recorded outcry of people smashing early wheels (as would happen with later inventions), perhaps because the benefits were immediately obvious and spread gradually. Nonetheless, one can imagine a few skeptics in Neolithic villages, eyeing the first carts with suspicion: Would these rickety contraptions scare the livestock? Were wheels unnatural? Such doubts, if they occurred, were quickly silenced by the wheel’s clear utility. The wheel made life easier and richer, allowing farmers, builders, and travelers to experience reality in new ways. It turned laborious tasks into rolling motion and opened the road—literally—for all subsequent innovations to come rolling after.

Writing and Printing: Inventions of Knowledge

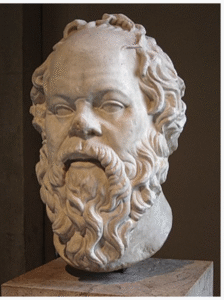

Socrates

If the wheel expanded our physical horizons, writing expanded our mental horizons. The invention of writing (in Sumer, Egypt, and elsewhere over 5,000 years ago) allowed humans to record ideas, history, and imagination outside the mind for the first time. Knowledge could accumulate and spread across generations. Yet this leap also met early resistance. In Plato’s dialogue Phaedrus, Socrates famously tells a myth of the Egyptian god Thoth presenting writing to King Thamus. The king criticizes writing, warning it will “produce forgetfulness” in learners by encouraging them to rely on written characters “which are no part of themselves” instead of truly understanding. Socrates feared that writing would give people “the appearance of wisdom” without real insight. Today we know writing was a boon to civilization—enabling science, literature and law—but in its infancy even this now-indispensable technology was seen by some as a threat to the mind’s natural abilities.

For millennia after, writing remained a specialized skill, guarded by elite scribes and scholars often under the patronage of rulers or religious authorities. Knowledge was copied by hand onto clay tablets, papyrus, and parchment – a slow process that kept books rare and learning largely in the domain of the few. This status quo prevailed until the printing press dramatically upended it in the 15th century. German inventor Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press (c. 1440) introduced movable type and mechanical reproduction of texts, making books cheap and information plentiful. It was a world-shaking revolution in the dissemination of knowledge – and it too provoked fear among those invested in the old ways.

A reproduction of Gutenberg’s printing press. This 15th-century invention shattered the monopoly of medieval scribes, allowing mass production of books for the first time. It sparked an information revolution – spreading new ideas far and wide – but was initially met with violent resistance from those who feared its disruptive power.

When the printing press began spreading across Europe, it threatened the livelihood of scribes and the control of knowledge by church and state. Establishment backlash was fierce. In fact, “when the printing press was invented, Scribes’ Guilds destroyed the machines and chased book merchants out of town,” viewing the device as diabolical. One early printer, Johann Fust, was accused of witchcraft in Paris and had to flee for his life. All over Europe, similar scenes played out: printers had their presses smashed and their shops burned by those who saw mass-produced books as dangerous. In 1501, Pope Alexander VI even threatened to excommunicate anyone printing books without church approval. The clergy feared an uncontrolled spread of information and heresy; monk-scribes worried about losing their copyist jobs; and scholars sniffed that cheap printed texts could never equal the beauty and authority of traditional manuscripts. As one resistant monk, Johannes Trithemius, argued in 1492: “Printed books will never be the equivalent of handwritten codices, especially since printed books are often deficient in spelling and appearance.” (Ironically, his anti-printing tract was itself printed on a press).

In hindsight, the triumph of the printing press seems inevitable. Gutenberg’s invention did not vanish under pressure; it proliferated and proved immeasurably beneficial. The press “transformed and catalyzed learning across the world,” spreading literacy and new ideas to millions. It helped fuel the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution by democratizing access to knowledge. Within a few centuries, books and newspapers became commonplace, and the very authorities who once opposed printing eventually used it to educate and inform. Today it’s almost impossible to view the printing press as “a disastrous blot on history,” yet “that’s exactly how many people perceived it at the time”. This pattern – extreme skepticism in the short term, obvious advantages in the long term – has repeated with many innovations, and we see it again in our own era with digital technology and AI.

The Perennial Fear of Progress

Why were Socrates, or the medieval scribes, so wary of new tools of knowledge? Simply put, people fear what they do not yet understand. Most of us are creatures of habit; big innovations disrupt the status quo, bringing change that can feel threatening. History shows that whenever a disruptive new technology arrives, a wave of anxiety and resistance often follows. As one commentator noted, “Most people, most of the time, hate change… when you get hate and fear, anger and suppression follow not far behind.” This technophobic reflex is part of being human. We worry what the world will look like after the new invention, just as King Thamus worried how writing would change minds, or scribes worried how printing would change society.

Consider a few more examples: In the 19th century, the Luddites (textile workers in England) smashed automated weaving machines, fearing the new looms would destroy their jobs. Early locomotives and automobiles were met with public skepticism; some even believed the human body couldn’t survive the “tremendous” speed of 30 mph, or that automobiles should be preceded by a person waving a red flag to warn pedestrians. When home electricity was introduced, many worried that houses might spontaneously combust or that “invisible” electric currents were harmful. Even the humble light bulb was once mistrusted by candle makers and those afraid it would disturb sleep patterns. Each of these fears seems quaint now, yet they were genuine in their time.

Fast-forward to the late 20th century: personal computers and the internet also had their share of doubters and doomsayers. In the 1980s, some feared that computers (termed “electronic brains”) would eliminate white-collar jobs en masse or even override human decision-making. In the 1990s, as the internet went public, critics warned of information overload, loss of privacy, or moral decay via online content. To be sure, new technologies do bring new challenges – job roles change, skills must adapt, misinformation or misuse can occur. But history teaches that society adapts. We develop new norms, regulations, and practices to integrate the technology and mitigate its downsides. The printing press, for example, did enable the spread of false pamphlets and dangerous ideas, but over time we developed journalism standards, libraries, and educated publics to filter truth from falsehood. Likewise, industrial machines did disrupt labor patterns, but they also created wealth and eventually more jobs in new fields, raising overall living standards. In short, everything ended up alright – not by ignoring the risks, but by confronting them with human ingenuity and ethical guidelines.

This historical perspective should give us confidence as we face the latest transformative technology: artificial intelligence. The moral and ethical dilemmas AI raises are real – just as with fire (which can cook or burn), the wheel (which can carry or run over), or the gun (which can defend or destroy). But the lesson is clear: we should not fear the tool itself, but rather focus on the intentions and actions of the user. As the saying goes, one need not fear the gun but the gunman. In the same vein, AI in the hands of a malicious actor is worrisome, but AI itself, like any tool, has no intent – its impact depends on how we choose to use it. Oren Etzioni, a prominent AI researcher, put it succinctly:

“AI is neither good nor evil. It’s a tool. The choice about how it gets deployed is ours.”

— Oren Etzioni

In other words, AI will be what we make of it. With responsible use, it could dramatically improve the human experience – akin to past innovations like fire, the wheel, and the printing press – ushering in a new era of possibility.

Artificial Intelligence: The Next Frontier of the Mind

Today’s advances in artificial intelligence represent the next great leap in humanity’s toolmaking odyssey. In a very real sense, AI is an extension of our own imagination and intellect – a “thinking tool” that we’ve created. Just as the wheel amplified our physical motion and writing amplified our memory, AI has the capacity to amplify our cognition and creativity. Rather than replace the human mind, it can serve as an augmentation of it. Indeed, leading technologists emphasize that AI will “augment human intelligence rather than replace it,” working in partnership with people across domains. AI is often likened to a general-purpose utility, the “new electricity,” because it may ultimately power improvements in every industry from medicine to transportation to education. Andrew Ng, one of the pioneers of modern AI, notes that electricity transformed countless facets of life, and “AI is the new electricity” poised to do the same

Already, we see AI being used as a collaborator and creative catalyst in fields that were once exclusively human. In the arts, for example, generative AI models can compose music, create visual art, or assist in writing. Rather than making human artists obsolete, this technology often acts as a creative muse – sparking new ideas and combinations that the artist can then refine. “Forget about automation. AI is augmenting human creativity in ways we never imagined. It is a brush in the hands of painters, a muse for musicians, and a collaborator for writers,” writes one observer, calling AI “a catalyst for a new creative renaissance where human ingenuity and machine intelligence coalesce.” In music, tools like AI-assisted composition can generate novel melodies or harmonies, which composers incorporate into their work. In visual art, systems can generate images in various styles, giving artists fresh inspiration or helping them visualize concepts. Writers use AI-based assistants to brainstorm plots or even draft portions of text, which they can then edit with their personal touch. Rather than AI replacing human creativity, the experience so far suggests it enhances and expands our creative reach. The machine can churn through permutations at lightning speed, but humans provide the vision, taste, and final judgment. As such, AI often acts as a co-creator. It offers “new sonic textures, patterns, and harmonies that humans might not naturally conceive,” expanding the toolkit available to musicians and artists. These examples reinforce that AI is an enabler, not a usurper, of human creativity.

Beyond the arts, AI has tremendous potential to advance science, education, and daily problem-solving. In science and medicine, AI systems can analyze vast datasets far faster than any person, identifying patterns or solutions (e.g. new drug candidates, optimized engineering designs) that would have taken humans years to discover. In education, AI tutors and language models can provide personalized learning, bringing quality instruction to students who might otherwise lack access. By automating repetitive tasks, AI can free teachers and professionals to focus on more creative and meaningful work, rather than drudgery. For instance, AI can grade routine assignments or sift through research archives in seconds, allowing a teacher or researcher to spend more time on understanding concepts and mentoring others. In business and everyday life, AI assistants help schedule our calendars, recommend useful information, and even translate languages on the fly – effectively breaking down communication barriers and putting a wealth of knowledge at anyone’s fingertips.

Crucially, AI is also lowering the barrier to innovation and invention. A generation ago, someone with a great idea (like a clever gadget or a new software concept) but without specialized skills or funding might have been stuck at the idea stage. Today, that same person can use AI-powered tools to prototype, program, or troubleshoot their idea with relative ease. For example, an aspiring inventor can ask a generative AI to draft a circuit design or suggest improvements to a mechanical sketch; a novice programmer can have an AI co-pilot write and debug code for an app; a student with curiosity can query a chatbot on any topic and get a coherent explanation or a creative solution. In this way, AI acts as a kind of intellectual equalizer – a tutor, assistant, and brainstorming partner available 24/7. This democratization of expertise means more people than ever can turn imagination into reality. Like the author of this essay realized how working with AI improved his vocabulary and thinking, even making him “feel younger” as he engaged in constant learning and idea exploration. Such anecdotal evidence points to a broader truth: when wielded with curiosity and openness, AI can sharpen our minds by exposing us to new words, concepts, and perspectives at lightning speed.

None of this is to say that AI comes without challenges or risks. Like fire, which can heat a home or burn it down, AI is a double-edged sword. We must address serious questions: How do we prevent bias in AI decisions? How do we protect privacy and ensure AI isn’t used for malevolent surveillance or misinformation? What about the impact on jobs and the economy as AI automates certain tasks? These are valid concerns being actively debated by ethicists, policymakers, and the AI community. It is encouraging to see that AI’s creators and users are not blind to these issues – there is a global conversation about ethical AI, responsible deployment, and the need for sensible regulations. As Apple’s CEO Tim Cook urged, “What all of us have to do is to make sure we are using AI in a way that is for the benefit of humanity, not to the detriment of humanity.” In other words, human values and wisdom must guide AI’s development. This is akin to how society eventually put safety standards around electricity, established laws for automobile use, or agreed on protocols for nuclear technology. The tool can be powerful, but we remain the moral agents who decide how to wield it.

And here is the hopeful insight from history: we can get this right, because we’ve done it before. Each time humanity encountered a disruptive new capability – whether it was the fire that could destroy a forest or cook dinner, or the printing press that could spread enlightenment or libel – we learned to maximize the good while managing the bad. We adapted. There is nothing mystical or supernatural about AI; as one AI pioneer noted, “there is nothing artificial about it. AI is made by humans, intended to behave by humans, and, ultimately, to impact humans’ lives and human society.” In short, AI is a human tool, born of human imagination. It does not exist apart from us; it is an expression of us. Just as a hammer can build a house or be a weapon, AI can compose a symphony or generate malicious code – but the choice lies with its human users and designers. If we approach AI with the right intentions, knowledge, and caution, we have little to fear from the tool itself. As with the wheel, the real danger is not that the wheel exists, but whose hands are on the wagon and where they choose to steer it.

Embracing a New Renaissance

Looking back, we see a remarkable narrative of human progress driven by imagination: We harnessed fire and lit the dark; we fashioned the wheel and bridged great distances; we invented writing and preserved wisdom; we built printing presses and educated nations. Each step empowered us to experience reality more fully, to do and know more than our ancestors could have dreamed. Now, with artificial intelligence, we stand on the threshold of another leap – perhaps the greatest of them all. AI holds the promise of amplifying every aspect of human endeavor: creativity, communication, scientific discovery, education, and beyond. Some have even called this moment the beginning of a “mother of all renaissances,” one that could surpass the scope of any renaissance before, because it is fueled by tools that enhance our very thinking. In partnership with intelligent machines, we can envisage solving problems that once seemed intractable – from curing diseases to reversing climate change – and also enriching our daily lives with more art, knowledge, and connectivity.

To reach that bright future, we must overcome the stigma and fear surrounding AI. It is normal to feel uneasy when confronted with something as novel and powerful as AI – just as our forebears felt about the printing press or the locomotive. But if we let fear dominate, we risk stifling one of the greatest opportunities in human history. Instead, let’s begin a thoughtful conversation about how to use AI wisely. We should ask: How can AI improve communication and understanding among people? How can it expand access to education and expertise globally? In what ways can AI foster benevolence and empathy (perhaps by detecting mental health issues and encouraging people to help one another)? How can AI collaborate with us to create art that moves the soul or to accelerate scientific discoveries that save lives? These are the discussions that matter, and they are far more constructive than dystopian nightmares.

Importantly, embracing AI does not mean naively ignoring its pitfalls; it means actively shaping its development to align with our highest values. It means setting rules of the road (much as we did for cars and planes) so that this powerful engine is guided by human conscience. It also means investing in educating everyone – not just engineers – about what AI is and isn’t, so that society at large can participate in this new renaissance. The invention of the wheel ultimately benefited all of society, not just the first wheelwrights, because people learned how to use wheels everywhere. Similarly, AI’s benefits should be widely shared, and that requires broad understanding and engagement.

In working with AI, many people (myself included) have found that it actually enhances human thinking rather than dulling it. A dialogue with a smart AI can challenge you with new vocabulary, new ideas, and instant feedback. It can be like holding a mirror to your own thoughts, prompting you to clarify and improve them. Far from making us lazy or unimaginative, AI can push us to be more creative and curious – if we approach it with the right mindset. Imagine a future where everyone has a tireless tutor, a personal research assistant, and a creative partner at their side. Such a future could unlock human potential on a vast scale. We might see an explosion of grassroots innovation and creativity, as people who previously didn’t have access to certain skills or knowledge can now tap into AI’s assistance. This democratization of intellect and creativity could lead to a flourishing of art, science, and culture beyond anything in our past – truly, a new Renaissance powered by AI.

The wheel, the printing press, the computer – each was a tool for humanity’s mind and will. Artificial intelligence is no different. It is born from our imagination and now gives us a tool to imagine even further. As we have always done, we must wield this new tool with wisdom and moral responsibility. We must be vigilant against misuse, certainly – the “gunmen” who might aim the tool for harm – but we must not lose sight of the immense good that is possible. History tells us that the benefits of embracing a transformative invention, guided by conscience, far outweigh the risks of stagnation. Fire warms far more homes than it burns; the printing press educated far more people than it misled. Likewise, AI stands to help far more humans than it hurts, if we steer it with care.

In the final analysis, God (or genius) is indeed our own human imagination – and AI is an extension of that imagination, made tangible. It is a projection of our thought processes into a new form, much as a telescope extends our eyes or a wheel extends our feet. Rather than view AI as an alien usurper, we should recognize it as ourselves, in tool form: our ingenuity, curiosity, and creativity amplified by a new kind of partner. By shedding the stigma and embracing this perspective, we empower ourselves to guide AI’s growth in a positive direction. Let us therefore approach artificial intelligence with the same boldness and thoughtfulness that marked the adoption of the wheel and every great invention since. If we do so, we can step into a future where technology and human mind work in harmony – a future in which we experience reality to the fullest, enhanced by the very tools of our own creation. It is a future waiting for all who are willing to listen, learn, and participate in this grand conversation. The wheel has turned, and a new chapter begins – let’s get the ball rolling.

Sources: The historical and analytical insights above are supported by a variety of sources. Early skepticism of writing is exemplified by Plato’s account of Socrates warning that writing would weaken memory and give only the “appearance of wisdom”. The revolutionary impact of the wheel is well documented as “one of humanity’s most transformative innovations,” enabling humans to “conquer distances…and shape the world as we know it.” Fire’s central role in human progress (and even human evolution via cooking) is affirmed by research noting that “without a doubt, fire has proved a primary mover in the evolution of civilization,” essential to developments like metallurgy, agriculture, and migration. The violent resistance to Gutenberg’s printing press is recorded in historical analyses – for example, guilds of scribes destroyed early presses and religious authorities censored unauthorized printing, fearing the spread of misinformation and loss of control. Nevertheless, the long-term benefits of the press in spreading knowledge and catalyzing progress are universally recognized. This pattern of initial fear yielding to eventual societal benefit is further echoed in modern commentary comparing past and present tech reactions.

Regarding artificial intelligence, expert perspectives emphasize its nature as a neutral tool under human control – e.g., “AI is neither good nor evil. It’s a tool… The choice about how it gets deployed is ours,” as stated by Oren Etzioni. Industry leaders liken AI’s transformative potential to that of electricity in its ubiquity and utility. Far from replacing human creativity, AI is increasingly seen as a collaborator: “a brush in the hands of painters, a muse for musicians, and a collaborator for writers… a catalyst for a new creative renaissance” where human and machine creativity combine. Examples from the arts and journalism show AI acting as co-creator and assistant rather than usurper. Finally, leaders urge a focus on ethical, beneficial use of AI – “using AI in a way that is for the benefit of humanity” – underscoring that we hold the responsibility to shape this technology’s impact. All these sources reinforce the essay’s core message: from the wheel to artificial intelligence, human ingenuity has continually overcome fear to leverage tools for the advancement of our civilization.